-

I picked the dandelions in a cemetery, two years ago. Now the cemetery is gone.

Thomas Pynchon, The Crying of Lot 49

-

Many blogs read as if the user sees him- or herself at the center of the world, with his or her posited audience hanging on every action the blogger takes—almost as if the blogger was a different order of human being from the blog’s readers.

David Golumbia, The Cultural Logic of Computation

-

The 20/20ness of the Nintendo Switch's success

Nintendo announced the Switch 2 today. The conventional wisdom is that it’s “boring,” but in a good way—finally, Nintendo has settled down into an almost Sony-esque cadence of numbering its consoles in sequence. The Verge’s Andrew Webster summed up this view:

Really, the form factor of the Switch didn’t need changing. It’s clear consumers loved it; Nintendo has sold more than 146 million of them, as the Switch inches closer to toppling the DS as the company’s bestselling piece of hardware. It’s flexible in a way that made sense for a large group of people, and it helped spearhead a renewed interest in portable gaming, one that is now taking the PC world by storm. Even Microsoft and Sony are tentatively getting into the space. And by merging its portable and console development teams, Nintendo was able to focus on a single device and greatly improve the cadence of new releases. Over its eight years of existence, the Switch had surprisingly few lulls between major new games.

The Switch will outsell the DS and may yet dethrone the PlayStation 2, despite the latter having the enormous advantage of having been the first and only DVD player that many people ever owned, right at the peak of the physical media era (2005, the year before the PlayStation 3 and Blu-ray Disc tech came out, was the top year for DVD sales). A portable console that can output in HD to your TV seems blasé now, a surefire winner. But it wasn’t obvious at all in 2016.

Surviving the smartphone gaming era

In the run-up to the Switch’s unveiling that fall, there was a lot of confused talk about how Nintendo was building a cartridge-based system, in an era in which its two rivals (the PlayStation 4 and the Xbox One) were all-in-one media centers with their Blu-ray drives. It seemed like a recipe for doom, especially on the heels of how badly the Wii U had sold. Nintendo hadn’t sold a cart-based home system since the Nintendo 64, which, while fondly remembered by some millennials today, was a major failure in that it permanently ceded a huge segment of the gaming market to Sony, and mostly on account of its usage of expensive, low-capacity carts at a time when cheap, high-capacity CDs were becoming the norm.1

The 3DS—the DS’s lookalike successor—was the only thing keeping Nintendo solvent during the lean 2011-2017 era, when Wii-mania had ended and almost no one seemed interested in its successor. Even its success was qualified—though it sold over 75 million units, that was only about half of the DS’s haul. Moreover, the idea of a dedicated handheld with a ton of buttons seemed antiquated in the era of smartphone gaming.

The early and mid 2010s were the “smartphone gaming” era, when gaming on your phone felt novel and limitless in its possibilities. I remember seeing a bar graph on Business Insider about how Angry Birds had already “outsold” the entire Super Mario series. The simplicity of touch controls plus the ability to add overlay controls onto a touchscreen (i.e., virtual buttons) seemed like the “end of history” for mobile gaming.

In a 2013 post cheekily titled Nintendo in Motion2, John Gruber said:

Nintendo is doing poorly because they seem incapable of producing best-of-breed hardware, both in console and handheld. The world has changed in the last five years, and hundreds of millions of people now carry powerful, well-made, touchscreen computers with them everywhere they go. Nintendo should expand to start making games optimized for these devices—in the short term as [an] opportunity to sell more games, in the long term as a hedge for the possibility that the company will no longer be able to compete at all in hardware.

He was responding to a Lukas Mathis post that had said “Mac analysts” (a catch-all term for Apple-focused bloggers like Gruber) had an obsession with Nintendo that resembled the obsession Microsoft analysts once had with Apple (thinking it should just stop making hardware, etc.)

Nowadays, Mac analysts have a similar obsession with Nintendo. The logic goes a bit like this: Nintendo is doing poorly because Apple and Samsung own the market for portable devices. If only Nintendo stopped making hardware and published their games for iOS instead, surely, it would do much better.

Mac users should understand why this argument is flawed. Fantastic games like Super Mario 3D Land can only exist because Nintendo makes both the hardware and the software. That game simply could not exist on an iPhone. Nintendo makes its own hardware because that allows it to make better, more interesting, unique games.

But there’s an additional problem with this argument: the premise is completely wrong. Nintendo is actually not doing poorly in the portable market. iPhones have not destroyed the market for portable gaming devices. The 3DS is, in fact, doing very well.

Gruber turned out to be completely wrong whereas Mathis was completely right. In fact, the success of the 3DS was a turning point in gaming history, although it wasn’t recognized at the time and maybe not even now.

How the 3DS changed the game

The 3DS was widely perceived as just a DS with stereoscopic (glasses-free) 3D technology and maybe a little more horsepower. In reality, it was ridiculously capable for a handheld gaming device:

- It was in practice almost as powerful as a PlayStation 2, with the ability to run complex games such as Dragon Quest VII, Super Smash Bros. For 3DS, Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater, and Xenoblade Chronicles3. The “3D” in its name wasn’t just about the stereoscopic effect, which was largely gimmicky—it was also about the console’s plethora of fully 3D titles, games that the original DS couldn’t possibly have run.

- It had an analog stick (and a camera stick on later models) and tons of buttons, plus two cameras.

- Also, it was compatible with the entire DS library.

Nintendo priced it very high, seeming to realize it had built a colossus. But it took a while for people to catch on. The price was quickly cut and it was only in 2013 that the release schedule finally started humming with titles such as The Legend of Zelda: A Link Between Worlds and Luigi’s Mansion 2. As Mathis noted, these types of games, with their clever use of the dual screens and complex controls, were simply impossible on the featureless face of an iPhone.

Rather than an antique avatar of a bygone dedicated handheld age, the 3DS was the herald of a new era in mobile gaming, when tiny bespoke hardware could run titles that phones and tablets couldn’t touch and that rivaled home consoles and PCs in their complexity.

Even now, the 3DS’s library is astonishing in its depth, with everything from addictive puzzle games to mature-themed visual novels. The only Nintendo console with a similar depth and breadth of titles is the Switch, which I think is better thought of as the successor to the 3DS than the Wii U.

The iPhone moment for console gaming

With its ability to read Amiibo, its use of ROM cartridges and microSD cards, its ARM processor, its dual sticks, and its big screen, the Switch is like a slightly tweaked New 3DS4. The original Switch instantly made other gaming options, whether less (phones, tablets) or more (PCs, home consoles) complicated seem instantly outmoded, in the way that the original iPhone did for flip and feature phones in 2007. Gruber sees this:

That it’s just a bigger faster Switch is proof of the genius of the Switch form factor, which has now been widely copied across the industry. The Switch is to handheld + dockable console gaming what the iPhone is to phones.

Its variety of buttons and sensors made smartphone gaming seem too simple; its instantaneousness and portability made hulking PCs and consoles seem like heavy, slow, power-hungry dinosaurs. The only traces of the Wii U were (sort of) the tablet design from that console’s controller, but again, I think the form factor of the 3DS is a closer analog.

It shocked me at the time, in a way I don’t think any of its successors may ever do. Its success is maybe the best example I can think of the “hindsight is 20/20” cliché, but to really see why it was set up for success from day one, you have to see the 3DS for what it was—a signpost to the future rather than the past, maybe even “Nintendo’s iPod,” in how it led to “Nintendo’s iPhone” (the Switch).

-

The Switch represented Nintendo’s final divorce from optical disc technology, which had bedeviled it for almost 30 years at that point. The Super Nintendo Entertainment System was supposed to have had a CD-ROM attachment made by Sony, but the parties fell through and it became the PlayStation 1; the Nintendo 64 lost big to the PS1 because of how much easier CDs were to develop for; the GameCube, Wii, and Wii U all ran on proprietary optical disc formats designed to avoid paying royalties to Sony et al., but which came with the drawback of lower capacity than either generic DVD or Blu-ray. Now, optical discs are far too slow to actually run games from (PS4/5 and Xbox games are simply copied from the disc to the internal drive) and they put a major constraint on form factor. Neither is true of ROM carts, which remain super-fast, can be really tiny, and now can hold tons of data. ↩︎

-

A reference to Research In Motion, the old name of BlackBerry. ↩︎

-

This only ran on the New 3DS, which had extra processing power and more inputs (two more shoulder buttons and a second analog stick) ↩︎

-

In addition to the more powerful ARM processor, extra buttons, and second stick, the New 3DS had a built-in Amiibo reader and used microSD cards rather than full-size ones like the original 3DS. ↩︎

-

2006 music reviews rocked:

The Web site … shows a NYC apartment populated by, among other things, a sketchy rumpled bed (ew), bright red oversized American Apparel underwear (double eww), a Serge Gainsbourg record (triple ewww), and (pre-emptive quadruple ewww) The Village Voice.

-

Tonight’s game is The New Addams Family Series for the Game Boy Color, played on a glow-in-the-dark Analogue Pocket. One of the most technically impressive GBC titles, with gorgeous graphics and lots of dialogue.

-

A blog-shaped peg in a social media-shaped hole

Follow for follow is an ancient scam: A complete stranger looking to growth hack1 their account follows you (on X, Instagram, wherever) and then immediately solicits you to follow them, too.

Whereas you’re likely posting only the highest quality content2 and of course deserve the follow, they’re almost invariably posting hashtag-laden garbage while also following thousands of accounts—well beyond what anyone could actually keep up with. They’re not on the platform to interact or listen to anyone but themselves; their vast follow count means they practically can’t do anything else. To follow them is to make their number go up while polluting your own feed with unreadable, demoralizing, and relentless posts, in a darkly cute microcosm of how the logic of social media intersects with that of the stock market and environmental degradation.

With the advent of private Instagram accounts and the decline of the hashtag as an earnest form of engagement3, the follow-for-follow scheme was one I’d assumed had become an extinct-in-the-wild species in the social media ecosystem: not gone, but rare enough that it’s appearance was startling against the noise of the new normal.

Asymmetrics on Bluesky

But Bluesky, the would-be X/Twitter successor, has become a virtual wildlife refuge for follow-for-followdom. This is like the woolly mammoth coming back to life (ironically, not on Mastodon), or perhaps in a better metaphorical fit, the quagga, except with new and slightly ahistorical stripes. Indeed, Bluesky—due to the confluence of its libertarian rules and a matching attitude toward their enforcement plus its abundance of bored email job-havers—has reinvigorated follow-for-follow as a matter of social justice.

Here’s the outline, with an example:

- Let’s say Account A, with its 35 followers, follows Account B, with its 3,500 followers.

- Account B doesn’t follow back, likely because it doesn’t recognize Account A and/or is “too swamped to vet it and decide if a follow is merited.

- Account A sees this lack of reciprocation as an insult. Its operator thinks they deserved a follow-back, and that not getting it signals the arrogance of Account B.

Account A-type personalities have even coined a term for Account B counterparts: asymmetricals, as in “big” accounts that have numerous followers but relatively few follows.

This Bluesky post, which I’ll just copy and not link to (so as not to put the person “on blast,” even though I don’t have an audience sufficient to even “blast” them), sums up the stance and even has a tacky hashtag to go with it and emblazon the follow-for-follow legacy:

HChoosing [sic] not to follow back can signal a belief that you’re above your followers. It suggests their opinions don’t hold weight in your world. Social media is about connection, not superiority. Let’s remember: engagement should be mutual, not one-sided. #SocialMediaDynamics

It’s indisputable that the “big”4 accounts on Bluesky are descriptively asymmetric. They often follow very few people, and some rarely repost or quote anyone. On X/Twitter, this behavior once reached a comical extreme with the widely followed nominal leftist account zei_squirrel, who had thousands of followers while following literally no one.

However, accounts like the above-quoted use the term “asymmetric” normatively, as a judgment holding that big accounts on Bluesky are being unfair by refusing to follow their followers. Their key claim is that “social media is about connection, not superiority”—they nominally want more engagement, a wish that they think is stifled by an elite group of relatively big accounts who only want to hear themselves and their close circle talk.

What a bunch of crybabies, right? Or at least that’s the prevailing (and predictable) reaction from “big” Bluesky accounts, who see the new wave of follow-for-follow acolytes as children with naive and unworkable notions of fairness. “They’re not owed anything” and “I’m far too busy to engage with randos” are fair summaries of this mentality, and I can partially endorse the first sentiment5 at least considering that many accounts seeking follow-backs are indeed just bad-faith growth hackers seeking to build their personal brands (I just puked writing that sentence). You’d have to be a real self-loather to follow all of them, for ideological and practical reasons.

Buuuut (you knew that was coming), I don’t think the sudden wave of backlash at “asymmetrics6” is entirely frivolous, nor is its timing (as Bluesky siphons off some users from X) an accident. Not everyone annoyed with “big” accounts is a growth hacker. Moreover, the perceptions of such accounts as out-of-touch, self-absorbed broadcasters were decisive in Elon Musk’s transformation of Twitter and in the overall decline of social media (but perhaps not social networking) as a useful tool for the public.

Social media vs. social networking

First, a note on “social media” as a term, and its relation to the similar concept of “social networking.” Ian Bogost has succinctly differentiated them:

The terms social network and social media are used interchangeably now, but they shouldn’t be. A social network is an idle, inactive system—a Rolodex of contacts, a notebook of sales targets, a yearbook of possible soul mates. But social media is active—hyperactive, really—spewing material across those networks instead of leaving them alone until needed.

The shift from social networking to social media occurred circa 2009 for Bogost, and this squares with my own experience: That was the year that baseball manager Tony LaRussa sued Twitter for an account impersonating him, leading to the “blue checkmark” system under which Twitter (the company) individually verified the accounts of high-profile figures to prove they were who they said they were. This verification took the visual form of a blue (or white, if you were in dark mode) checkmark next to the account’s display name.

Verification put “big” accounts at a distinct remove from everyone else. Ny doing so, it also signaled how social media was more like broadcast media than an internet chatroom. Some accounts were just going to be Too Big To Interact With.

Although Twitter was always much smaller than Facebook (the platform it was often mentioned in the same sentence with), its novel verification system and one-way follow structure made it a sensation among journalists and the perpetually bored in its early years. For the media—who along with public figures were among the earliest blue/white checkmark bearers—there was the prestige of being visibly “verified,” like online recipients of a knighthood or other Birthday Honours title. For everyone else, instead of having to jump through the two-way follow hoops of Facebook (that is, sending a follow request to someone and then waiting for it to maybe be approved), you could just follow someone on Twitter and then consume their tweets much like you would blog posts in an RSS reader.

Whereas you’d use old-Facebook7 to build real connections with people you knew, you’d use Twitter to keep up with a lot of strangers, many of whom would not want to (and indeed would not) interact with you, even though the site’s setup made you think such interaction was inevitable and expected. Verification and the dawn of the social media era ironically made Twitter more like an old blogging service, with a social networking-like feel of only interacting with your digital Rolodex, for its most prominent and active users, even as it became much more free-flowing and chatroom-esque for everyone.

The blog-like core of old-Twitter

This structure worked, in that it seemed to keep big and small accounts alike content, for a while because it so closely resembled ones that people knew from the late 2000s and early 2010s: Reading a blog, commenting on it, and adding its RSS feed to a feed reader. After all, Twitter was for years referred to as a microblogging service—a descriptor that was accurate long ago but that seems cringe and irrelevant now. The biggest accounts were, yes, like bloggers, and their followers like the audiences, in both actual membership and overall behavior, that some of them had once built on their blogs.

But Google Reader, by far the most popular RSS reader, shuttered on July 1, 2013. Blogging itself declined significantly as people shifted more posts off the open web and onto closed social media platforms. The relative silence and slowness of posting a blog and maybe seeing a few comments on it to which you could respond—and the corresponding flow of refreshing your RSS reader to see a trickle of new blog posts—was replaced with the infinite scroll of social media.

This shift, which coincided with the major growth of social media platforms, brought with it a breakdown in the expectations of how social media relationships should work: The old one, modeled on consuming a blog conservatively and from afar as a frequent reader and occasional commenter, gave way to a new one in which all parties were like participants in the same chat room. Replying, quote-tweeting (which was only added as a feature to Twitter in the 2010s!), and asking for follow-backs were normalized. During my first foray into using Twitter, my timeline was flooded with people with virtually no followers of their own @-mentioning massive celebrities to tell them to delete their accounts (or much worse) and engaging in other types of self-promotion, whether sharing a link to their site or cramming their tweets with hashtags like the follow-for-follow grinders.

Such interactions became inescapable during the 2016 election cycle as big accounts ended up predominantly as Hillary Clinton supporters and smaller ones as Bernie Sanders Stans. This dynamic in turn drove a lot of big accounts to disengage from most intra-Twitter conversations: They embraced Twitter’s suite of content filtering features to lock replies or at a minimum effectively ignore (by muting) any accounts with default profile pictures, unverified email addresses—and most important of all—without checkmark verification. Yet even as they treated Twitter like a blogging service with themselves at the wheel, the site still looked and mostly worked as a giant chatroom where anyone could talk to anyone. This ambiguity was never resolved, and it still bedevils every Twitter-like service, most of all Bluesky.

Anyway, one way to think about this behavioral shift is as the “big” accounts doubling down on the blog-like core that originally sat beneath Twitter, while the smaller accounts—many of which were part of their audiences!—moved on. Elon Musk’s 2022 purchase of Twitter can in part be understood as him intervening decisively on the side of the latter group.

What did Musk do soon after buying Twitter?

- He stripped all the verification checkmarks and then only re-awarded them if people either paid or were deemed by him to be significant public figures (e.g. the President of the United States). By far the group hurt the most by this change were the left-liberal journalists, academics, and activists who’d constituted a disproportionate share of all checkmarks on the site.

- He made it so links—the currency of the email job-havers who were Twitter’s most active posters—got down ranked , making it so that the only way to have high-visibility posts was to post just text, images, and videos that kept people on the site.

- He degraded many of the content filtering features, such as how the block function worked, so that accounts could no longer so easily avoid interacting with other users.

- He emphasized the algorithmic timeline that serves you posts it “thinks” you might like, rather than ones from accounts you’ve actually followed (thereby shattering the value of the followed-follower hierarchy).

I’m not saying any of these changes were good8, only that they clearly represented (even if by pure accident) Twitter finally being forced by a major capitalist to catch up with other social media platforms such as Facebook (which has long downranked news content of any sort) and TikTok (where there isn’t really a followed-follower hierarchy) by abolishing the blog-like structure of old-Twitter. In turn, the groups of people most likely to flee the newly christened X were predictably the ones who’d most benefited from the previous hierarchy: left-leaning, hyperactive (in Bogost’s sense reference above) posters who weren’t real celebrities or even YouTube-level stars raking in millions from their online activity, but who had been the main characters on a one-way (micro)blogging service cleverly disguised as a fully interactive two-way social media platform.

Or to frame it another way: Their escape to Bluesky, which has all the same issues as old-Twitter did especially post-2016, is them trying to fit a blog-shaped peg into a social media-shaped hole.

Bluesky is one-way for me, two-way for thee

The search for a “new-Twitter” that can fully replicate the old-Twitter that Musk destroyed has been mostly dispiriting for those involved, for this fundamental reason: Nothing today can combine the blog-like legacy structure of Twitter with the scale and excitement that accompanied early-days social media, before it became something more readily associated with mental health breakdowns, direct political messaging, and aggressive censorship. And to the degree that any network can feel like old-Twitter, it’ll then inevitably have to deal with the same issues that beset that site in its later years, namely the disparity between how certain big accounts see it as a one-way megaphone and smaller accounts see it as a two-way (multi-way, I guess) chatroom that everyone is equally entitled to commandeer.

Mastodon, the first would-be successor, blurs the lines between social media and social networking. It’s a simple concept that seems complex: Anyone can install the Mastodon software (which is free and open source) on their domain and by doing so, connect it to other sites that also run the same software. It’s similar to how email works. Just as the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (authored all the way back in 1980) lets email accounts from Gmail, Yahoo!, Outlook, iCloud, etc. communicate with each other, the ActivityPub protocol (a W3C standard) lets servers running Mastodon software interact with each other. Because there’s a bit of a learning curve, Mastodon users seem somewhat likelier to have deep connections with each other because after all, they too survived the gauntlet of making the service work for them, and they often come from similar (technical) backgrounds. Mastodon’s decentralized structure means it’s much harder to become the center of attention. Your server might be blocked by another, there’s no suggestive algorithm to boost your posts based on the size of your followership, and you have to self-verify through a website you own.

Threads, Meta’s Twitter clone, is for real celebrities and brands, not people. It buries posts beneath its algorithmic timelines, will soon be stuffed with promotions, and is overall basically just X run by Mark Zuckerberg rather than Elon Musk.

That brings us to Bluesky, which has succeeded to an extent in becoming “Twitter 2,” albeit at a much-reduced size. I’m on the record as a Bluesky bear. Like Bogost, who separately described Bluesky as a short-term “bubble” amidst the longer-term decline of social media, I think social media is fundamentally flawed in that overexposes us to the opinions of others, beyond a scale that we can manage. Bluesky doesn’t fix this; the entire site, which looks and feels like something from 15 years ago, makes no sense except as a successor-in-waiting to Twitter/X. On my since-deleted X account, I once likened its vibe to a high-school reunion for Twitter-famous posters: Awkward, insular, and maybe not a great idea.

And “succeed” it has, in replicating the old hierarchy and its accompanying issues in miniature. The site is dominated by erstwhile “big” accounts that fled Twitter and have re-established a reduced but still bigger-than-most following. This reduction in scale is important: Just as the “big” accounts are diminished compared to their previous presences on Twitter, so are the small accounts even smaller. This has, I think, been a catalyst for the follow-for-follow discourse, for these reasons:

- The small user base combined with the instant dominance of the “big” accounts that simply moved shop from X to Bluesky means that engagement is difficult unless you’re already big. Even though there are plenty of bad-faith growth hackers asking people to follow them back, there are also people who just want to get some (any) interaction on Bluesky.

- The big accounts are now operating at a reduced scale in terms of their own mentions and interactions. A “hit” post on Bluesky might have fewer than 1k likes (compared to tens or hundreds of thousands on X), and an ordinary one far less than that. That means that in theory, they should be able to read and acknowledge many of the interactions coming their way—something that would’ve been impractical at the scale of X.

- And yet big accounts often do completely ignore earnest replies, and forego any attempt to follow beyond a narrow circle of people who agree with them, while simultaneously interacting with trolls and annoying reply-guys. They might also talk about how busy they are, a statement somewhat contradicted by how they’re announcing that on a niche low-interaction social media platform. This behavior probably drives small accounts wild; “why are you ignoring me?”

At the same time, Bluesky like Twitter hasn’t resolved the tension between how its “big” accounts see and use the site and how everyone else does, and if anything the tension is worse because:

- The site is technically janky, without the polished functionality (like muting of unverified accounts, plus centralized verification that goes beyond its Mastodon-esque domain-name verification system) that once let the “big” accounts truly stand aside from everyone else.

- The reduced scale plus the growing distance from the one-time blog-like structure of Twitter means that people expect more interaction than they did on Twitter, even though that’s not possible even under the best of circumstances due to the sheer user numbers.

So, I think there’s something understandable in the frustration from accounts who don’t get followed back or even replied to, just as there’s something understandable in “big” accounts thinking such behavior is weird and Bluesky should instead be a one-way street for them to share their every utterance, trivial or profound, with their audience. Note that this exact dynamic doesn’t exist on, say, YouTube, where absolutely titanic accounts are never expected to follow or interact with you because the site makes it clear that you’re mostly there just to passively watch and then maybe briefly comment. Nor does it exist on Instagram (which is more celebrity-driven and distant, thanks to its relative dearth of text).

But on Bluesky, a “big” account looks like any other account, and the site makes you expect that you can interact with it directly.

And yet you get the sense that a lot of “big” accounts would almost prefer not having to interact with anyone—in which case you have to ask what value are they getting from the site, or from continued social media usage at all. Is their presence just some vestige that they can’t discard? Or do they just like hearing themselves talk and get adulation, free from thoughtful interaction? If the latter, they have a lot in common with the follow-for-follow hustlers after all.

-

This term has been so overused in Silicon Valley and in marketing departments that it instantly sounds dated and cloying, sort of like invoking fellow awkward terms such as “big data,” “biopower,” or as we’ll see, “microblogging.” ↩︎

-

I loathe this word. My podcast host and I have a whole show dedicated to how much it sucks. ↩︎

-

Mastodon, the self-hosted social media software that creates a Twitter-like service connecting different servers, is really the only place I’ve found where hashtags (which can be followed as if they’re accounts there) are used unironically and provide actual utility. ↩︎

-

I’m putting this in quotes throughout because we’re talking about like obscure professors with 5,000 followers, not Stephen King, who like many at his level only sparingly use any such platform, if at all. ↩︎

-

I don’t fully endorse because I really despise the similar Mark Twain-attributed sentiment that “the world doesn’t owe you anything; after all, it was here first.” The world absolutely owes you a decent life, otherwise how will it fucking replicate itself? As for the second sentiment, well…if you’re free enough to be posting on Bluesky regularly, how “busy” can you ultimately be? ↩︎

-

This comes off as a slur but it’s so esoteric and frankly low-stakes that I don’t think it’s harmful to reprint. ↩︎

-

Facebook was a totally different thing before 2012, when it went public and became much more algorithmic and ad-stuffed, and especially before 2006, when it had no main feed and was limited to .edu email addresses. ↩︎

-

Musk has made X a cesspool of reactionary discourse that endangers people’s lives. ↩︎

-

Old wine, new bottles, etc.

-

Two reasons Ebert’s gaming critique still stings and stirs:

- Games are impermanent compared to films, music, and books. Preservation is lacking, and the extinction of CRT TVs alone made many games unexperiencable in their intended forms.

- You indeed can’t “win” at art, but you can at most games.

-

Bluesky is a retreat

What are the major sources of left-liberal ideas and activism in the U.S.?

Academia, the labor movement, and primary-secondary education (teachers more so than administrators) are obvious mainsprings; we can also add swathes of the legal profession, Hollywood, pop music, and publishing. Indeed, “teacher” and “lawyer” are the professions most associated with donations to Democratic politicians and causes1.

These same professions were the drivers of Twitter’s decade-long pole position in shaping and delivering U.S. political discourse. From roughly 2012 to 2022, the site, despite being small compared to Facebook and even Tumblr (remember Tumblr?), was an unrivaled source of high-speed news and entertainment—with a well-curated feed, you could blow by breaking news (before the TV networks even got it), screenshots of obscure academic texts that supplied apt commentary on a current event, and dense insider jokes that in some cases escaped into the extremely offline world.

The Twitter tandem effect

Twitter had a tandem effect going, one that I believe is impossible to reproduce in the current era:

- It had hundreds of millions of casual users who’d joined it when it in particular and social media in general were both novel. The fact that it was so odd, limited, and text-centric didn’t matter in those early years, starting from its founding in 2006: It was one of the only options, and its name, like Facebook’s, became synonymous with a new mode of media production and consumption. Such casual users created the critical mass of a somewhat diverse and representative—this is important!—audience that made Twitter an influential media outlet.

- The left-liberal constituencies mentioned above were generally influential and powerful and produced a disproportionate amount of the conversation through their compulsive use of the site. To dip into the “replies” column of like a stay-at-home lawyer was to find literally hundreds of posts every single day, discussing anything from NBA minutiae to breaking political news. Such lonely power users catalyzed discourse and also became somewhat famous, often by getting coveted blue checkmarks (which were handed out liberally to journalists) to indicate their verified status. At the same time, the dominance of these users didn’t send conservatives running from the site. They were still pretty entrenched.

Why can’t this effect be recreated anywhere else? Because:

- Social media isn’t new and exciting anymore. It’s become a lot like TV, with all of its biggest platforms now serving as much video as possible, hosting tons of ads, and providing almost no freedom to shape your own consumption. Casual users have been captured elsewhere, on YouTube and TikTok most prominently, and aren’t necessarily willing to try any new site or service now. Accordingly, post-20162 social networks are echo chambers that star highly self-selected groups, rather than “town squares” that feature cross-sections of the public.

- The most important left-liberal constituencies, the one that fed Twitter’s content machine, are substantially weaker than they were even two years ago, when Elon Musk bought the site and then renamed it X. Hollywood and publishing are the most obviously diminished, but academia is also really imperiled and education has been beset by the COVID-19 crisis and voucherization. You could barely ask for a better example of the overall decline than the fact that Kamala Harris’s celebrity-heavy campaign came up short in a way that’d have been unimaginable for Barack Obama in 2012.

Smaller and more homogenous

Which brings me to Bluesky, the “is this the next Twitter?” du jour. There can’t be a “next Twitter” for the reasons above, but Bluesky seems like the closest thing to “old” (pre-Musk) Twitter. But how close is it?

Max Read captured the gulf between the two in a recent newsletter:

[T]he users who’ve been joining Bluesky en masse recently are members of the big blob of liberal-to-left-wing journalists, academics, lawyers, and tech workers—politically engaged email-job types—who were early Twitter adopters and whose compulsive use of the site over the years was an important force in shaping its culture and norms. (Some of those users have been on the site for a while, valiantly attempting to change Bluesky’s culture from “toxically wack” to “tolerably wack.”) … Part of what’s made Twitter so attractive to journalists is that it’s relatively easy to convince yourself that it’s a map of the world. Bluesky, smaller and more homogenous, is harder to mistake as a scrolling representation of the national or global psyche—which makes it much healthier for media junkies, but also much less attractive.

Twitter was attractive to journalists for that reason and for how it made journalists and their social circles the “main characters” of the site, through verification badges (which proved they were who they said they were) and a massive soapbox for their ideas. When the first exodus from Twitter happened in 2022, many of the site’s compulsive users tried Mastodon, only to run into various technical (what’s an “instance?”; is Mastodon a “website” per se ?) and cultural (beefing with the Linux nerds who love the service) issues. These issues are well-documented.

But one that I don’t hear about as much is that Mastodon, by its very anti-corporate design—in addition to no ads, it doesn’t verify any accounts: you have to do that yourself by embedding something on your website to prove that it and your account are connected; it also doesn’t promote any content and has no suggestion algorithm—refused to make them stars. They couldn’t port their mini-celebrity from the bird site to the elephant site3.

Humiliation rituals

Moreover, this humiliation ritual signaled how their professions and the elites at the top of them had declined alongside Twitter itself. It wasn’t just that Twitter was disintegrating; the very constituencies that’d powered it had either moved on (casual users flocking to TikTok, Discord, Joe Rogan’s podcast, whatever) or become too weak to drive the conversation (left-liberals, now powerless to overcome Musk’s myriad changes to how the site ranked and served content).

Threads, Meta’s Twitter clone, offered little refuge because it was focused on real celebrities, not the pseudo ones created by Twitter itself pre-2022. It also provided very little control of your feed. You couldn’t be a star, or control your own destiny.

So, in this context, Bluesky seems to ex-Twitter addicts like salvation. It has a straightforward chronological timeline, a somewhat minimalist design, and no ads (for now—remember this is a venture capital-backed platform that currently early has no business model and will need one soon). And most vitally, its small-pond nature means the blue checkmarks of yore are once again the stars. Yet, as Read noted, it’s a fraction of what Twitter is even now, let alone in its heyday. It’s small, ideologically homogeneous, and hostile—yes, hostile, as Adam Kotsko4 correctly labeled the site after he retreated from it October. The echo-chamber culture is harsh to outsiders, manifesting itself on this site as lots of blinkered liberalism and meaning about “unfair” The New York Times headlines5.

Once more into the retreat

Riffs on ancient Twitter jokes, fatphobic discourse about Ozempic/Wegovy, and complete nonsense by amateur failed statehouse candidates like Will Stancil filled my timeline when I experimented with the site before backing out. This is the next big social media site?

It felt more like one big retreat, not just from Twitter’s size, discursive centrality, and diversity, but from a string of cultural defeats—most pivotally, Musk buying the site in 2022 and Trump winning in 2024 long after he’d decamped from the site that had once done so much for his own political career, for his own echo chamber, Truth Social6.

Early in Trump’s rise to the top of the GOP, someone likened him to a warlord ruling over a failed state. This turned out to be inaccurate because the party wasn’t “failed” at all; it was actually ascendant. But this ruling-over-the-ruins picture reminds me of Bluesky today, where some metaphorical “big fish” finally have a “small pond” they can retreat to and in which they can remain themselves as the main characters once again.

-

It’s “business owner” for Republicans. ↩︎

-

2016 was when both TikTok and Mastodon launched. Nothing innovative has launched in the social media space since. ↩︎

-

These were the names that people tossed around for Twitter and Mastodon, respectively, in late 2022. ↩︎

-

I was mutuals with Kotsko on Twitter and briefly on Bluesky, but his combative and narcissistic (he’s always complaining about fights he instigates) online persona forced us to part ways. ↩︎

-

This was a cottage industry on Twitter, headed by an account called “NYTimesPitchbot,” and it seamlessly made its way to Bluesky. ↩︎

-

This network is based on Mastodon’s freely available code. ↩︎

-

It’s not the economy, stupid

For almost a decade now, U.S political commentators have been vainly searching for the answer to one question: If the economy is so good, why are people so unhappy (with it and with everything else)?

Implicit in this question is the belief that a “good” economy translates linearly into electoral victories for the party overseeing it. By this logic, Donald Trump should’ve never come close in 2016, should’ve lost badly in 2020, and should’ve again had no chance in 2024.

But it should also have meant defeat for Barack Obama in 2012 and for George W. Bush in both 2004 and 2000. Really, the last president who rode a “strong economy” to victory was Bill Clinton, whose lead strategist James Carville coined the “it’s the economy, stupid” phrase. The theory is trash, but it has a huge hold on the commentariat because it seems like hard science: If numbers good, ergo candidate who was in office while numbers good will also do good.

So these purveyors of the “economy” theory of politics are currently appalled not that Trump won but instead that he did it despite the “roaring” Biden economy: “Just look at the GDP growth! And jobless claims are low due to a tight labor market! Here, study this chart. How could the stupid voters hate this?”

If you were unlucky enough to be on Bluesky before Biden’s disastrous June 2024 debate, you might’ve encountered center-left “wonks”1 posting “Biden boom” at every bit of decent economic news, trying to create propaganda that would shape perceptions of a “good” economy—as close as they’ll get to admitting that the concept they hold so dear, of an objectively measurable and in this case supposedly good set of indicators completely detached from politics, is actually made up. Indeed, what if there is no “economy” to be “good” in the first place?

Samuel Chambers chronicled the mythology of the “economy” framing in his book There’s No Such Thing as ‘the Economy’, demolishing the idea that there’s some objective domain that can be neatly severed from politics and culture. Instead of some monolithic “economy” that everyone can interpret the same way, there’s just perceptions that span multiple domains of life. I might say I feel bad about “the economy” relative to four years ago because of the ravages of COVID-19, the inability of governments to maintain even the baseline of the pop-up welfare state from then, and the concurrent images of costly newly waged wars worldwide. No chart of changes in inflation showing a recent decline is going to affect that.

Basically, it’s foolish to say voters are wrong to hate what you insist is a “good” “economy,” because life isn’t lived discreetly through charts but instead continuously through intersecting experiences that—shudder the thought—often go outside the strict domains of economics and quantitative political science. Kevin T. Baker summed it up well in a recent post:

Now, in the wake of electoral defeat, center-left think tanks and wonks seem determined to continue to tell voters they’re wrong about their own economic reality. They point to charts and tables showing the strength of the economy, as if statistical aggregates and lossy indicators were, in some sense, more real than lived experience. The rhetorician Kenneth Burke liked to remind his readers every way of seeing is also a way of not seeing, that our frameworks and analytical lenses can obscure certain details even as they highlight others. In this case, an overreliance on quantitative understandings of economic life have led us into a situation where leading figures in the world of professional liberal politics mistook their statistical representations for the territory they were meant to map. Rather than admit that their understanding of economic reality might be incomplete, they’ve decided that voters are unqualified to speak for themselves.

-

a wonk is a self-satisfied guy who thinks he has the best grasp of any issue purely because he gets into obscure details of it, even if those details are irrelevant. Re: “the economy” debate, this mindset is particularly destructive because it dismisses the public’s broad perceptions (e.g., prices are too high…) in favor of smug, granular gotchas (…but prices are actually increasing more slowly if you factor in seasonal adjustments) backed by carefully plucked data. ↩︎

-

-

The Last Doomscroll

In the spring of 2006, I was detached—from following politics, from my coursework at college, from everything. Why I was so out of it, I can’t explain, even in retrospect.

The results of the 2004 U.S. presidential election, which had happened during my first year living away from home, had been immediately demoralizing, but I’d forgotten about them within days. My philosophy class that met the morning after had briefly discussed the situation in Ohio—wasn’t anyone going to do anything, it’s too bad that Bush won, and so on—and then it never came up again, not that and not anything political, even though I worked closely with the instructor for years afterward.

How I followed the results on election night 2004 is as unclear to me now as the rest of that class session after the opening political bit. I remember going to someone’s dorm and talking political shop with several students, but the decisive moment—when Bush was projected to win—never happened, for me. I wasn’t following along obsessively with vote tallies, but instead periodically going to the big news site homepages to get an outline. Earlier in the day, I’d walked across the city to my psychiatrist and he’d been excited; it really had felt like, for a few hours that afternoon and when the initial exit polls arrived, that Kerry might win, and the post-9/11 era (which already felt like it’d lasted a century) would end.

But 2005 was going to be even worse. Again I wasn’t tracking the play-by-play of Bush’s second term but I got my pain without even having to seek it out: This was my first full year on my own, and I struggled with my classes, my identity, and with the bits of news that slipped through while I was on my desktop PC back in my dorm. Katrina, the attempts at privatizing Social Security, the retirement of Sandra Day O’Connor. My main ways of following political news had evolved somewhat from the year before. Thanks to one of my suite mates1, I was reading blogs like Talking Points Memo (TPM), Eschaton2, and Raising Kaine3, which provided a drip-drip update on Bush-era minutiae that was easily ahead of what was on the major news sites or TV stations.

By the time 2006 and detachment arrived4, I still occasionally took the pulse of political news but had also resigned myself to a permanent sort of Bushdom. I’d really hoped for his defeat in 2000, his rebuke at the 2002 midterms, and his re-defeat5 in 2004, but nothing happened and I was out of a politically engaged mode. Twitter launched around this time.

It may have been as late as 2009 that I remained unaware of Twitter, due to my disinterest in most tech news until I began working in the industry in the 2010s. I think I found it when doing some research on a prospective date, and seeing an account that was mostly tweets like “How does Twitter work?”. How, indeed; the site seemed useless when I first discovered it. Tiny posts with inscrutable links, check-ins, maybe a photo. My late discovery meant I wasn’t yet on the site for the 2008 election cycle, which nevertheless I was much more engaged with than 2004 due to my blog consumption reaching my pre-unemployment peak. I learned of the moment of Obama’s victory by following along with the TPM editor’s blog feed.

This blog-checking remained my primary mode of news-gathering for the first half of the Obama years. I learned about the ins and outs of Obamacare negotiations, the rise of the Tea Party, and the Beer Summit. But my more visceral connection to politics still came through TV. I was sitting alone in my dusty studio apartment, desperately looking for work, when I watched the 2010 State of the Union address and heard President Obama talk about the need to tighten the government’s metaphorical belt for some reason. This premature call to austerity, when unemployment was in double digits and millions were losing their homes, is my view the skeleton key for understanding American politics til this day. It contributed to the 2010 landslide losses in the midterms, and to the 2011 negotiations with John Boehner that nearly resulted in massive Social Security and Medicare cuts, until Boehner blew up the deal because he couldn’t stomach the modest rise in taxes that the proposed deal would entail.

Anyway: The point being, I learned the most important political news not from the internet, but from simply watching someone on TV talk. My consumption of political news on Twitter began in 2011, surged during the 2012 cycle and reached its peak in the run-up to during the 2016 elections. Although I missed much of the 2014 midterm news cycle due to having to move across the country, that lapse was more than offset by how by late 2015 I was following guys with avatars of John Rawls and Disney’s Aladdin discussing the intricacies of the Iowa caucuses.

Twitter on election night 2016 was a dire place. Jokes about a cake shaped like Donald Trump’s face quickly gave way to despair at the big red map of Pennsylvania’s counties. The gut punch of his victory turned me and it seems like everyone else into Twitter junkies. From 2017 to 2021, I don’t think I forewent checking the site for even a single day. I scrolled it aggressively, looking for the breakthrough piece of news that would finally signal the waking from a nightmare. My doomscrolling6 brought me back to 2006 levels of detachment, even though my political news consumption was the polar opposite of what it had been then.

I see now that all this obsessive Twittering had positive effects for me or anyone else. I didn’t benefit or profit in any way, and I drove myself nearly insane reading snippets of bad news and extrapolating them out to truly awful scenarios, most of which never even materialized. People said I seemed different, slower moving, more aloof. The only silver lining of the 2024 election was that it made finally leaving the site7, and returning to my old detached outlook (but with some introspection, I guess) all the easier.

Make it 2006 again, by science or magic; I’m back to reading news via RSS feeds, the occasional flick-on of TV, and in actual magazines and newspapers. Social media, something that really took form when I was in college and then quickly outran its own utility in the 2010s, becoming instead a dangerous set of politically polarized latter-day chatrooms. It’s literally hazardous to my health to doomscroll, so I don’t. I’ll be on Mastodon, and even then mostly as a place to auto-post my missives from here, and nowhere else. 2024 was the year of Alex and The Last Doomscroll.

-

I had my own room that academic year, but there was a shared common space and bathroom. ↩︎

-

An Infinite Jest reference. ↩︎

-

A reference to Tim Kaine, then a candidate for Virginia governor. ↩︎

-

Now that I look back on what I said earlier, I think the proximate cause was my inability to finish a Greek history course. That memory still hurts. Anyway, I made up for it with a class in 2006. ↩︎

-

When I first arrived on campus for a tour before I committed to going to the school, we saw a car with a “Redefeat Bush” bumper sticker right before we parked. ↩︎

-

This great neologism came from Twitter itself, and captures what it was like to just passively scroll through wave after wave of terrible news. ↩︎

-

I hardly need to explain that the site is now named X and is overrun by right-wing propaganda as per the wishes of its owner. ↩︎

-

-

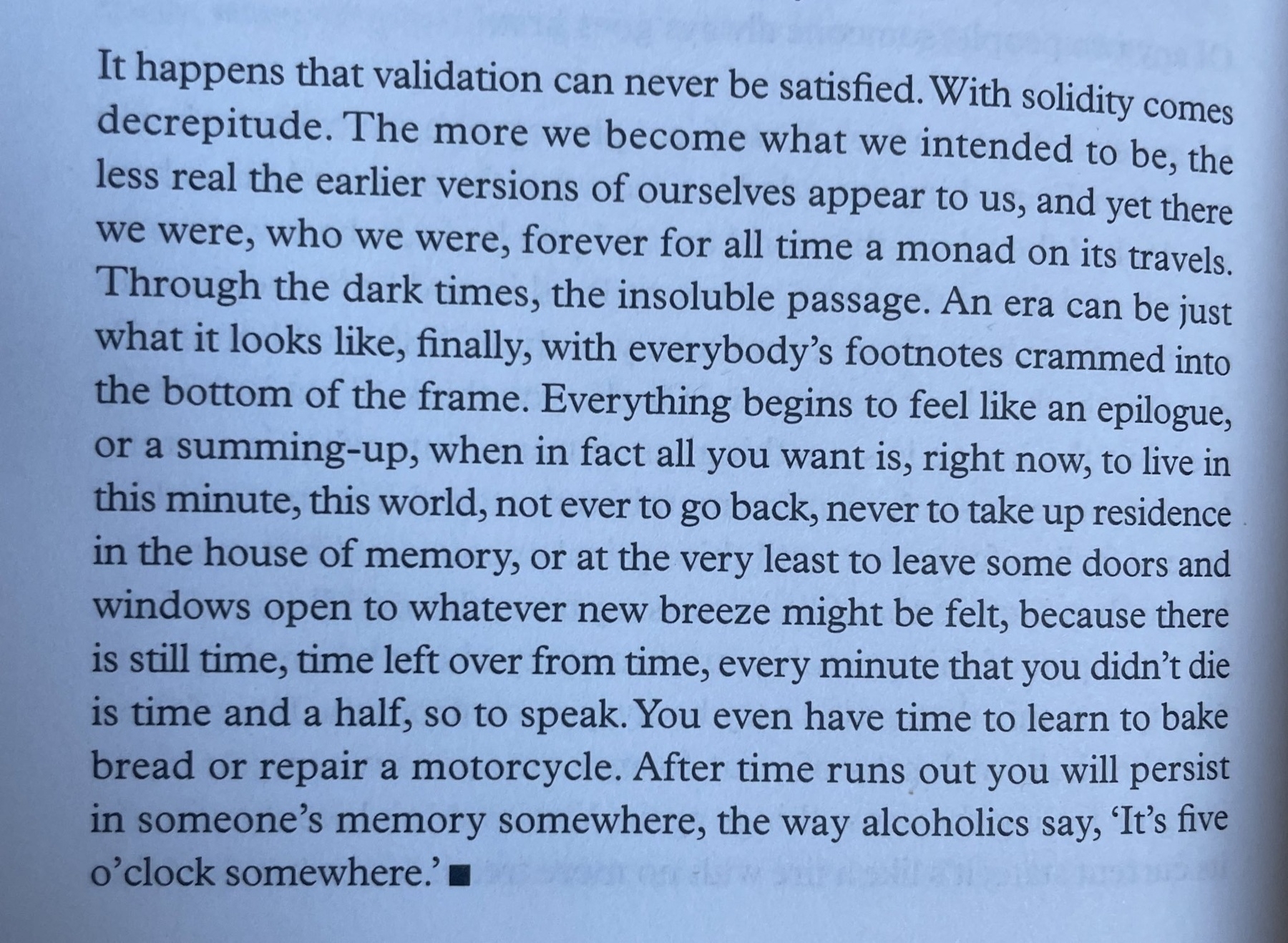

The last paragraph of Gary Indiana’s Five O’Clock Somewhere (screenshot by Ryan Ruby)

-

Andreas Malm and Wim Carton in Overshoot:

And what was the world capitalism built? An overheated and dried-out Guangdong province, serving shopping malls on all continents from its factories, choking on itself, grasping for even more coal to keep breathing a while longer.

-

From Stephen King’s The Gunslinger:

The eyes were damned, the staring, glaring eyes of one who sees but does not see, eyes ever turned inward to the sterile hell of dreams beyond control, dreams unleashed, risen out of the stinking swamps of the unconscious.

-

The falling leaves reveal the shape of the wind. Its breath blows its disguise by sucking their life from the air into a hidden bellows, to heat the smelting of new gold, red, and orange geometries. Each leaf is an orphaned shape, its edges fitting with pieces lost in scattered wind and unseen fire.

-

The Last Unicorn, 1982

-

The leaping and creeping ritual in Gulliver’s Travels—where contestants jump over or duck under a stick held by the Lilliputian emperor, with the winner being awarded high office—is only a bit less absurd than the U.S. Electoral College. Anyway, here’s Peter O’Toole playing the Lilliputian emperor.

-

What is sound?

What is sound? Yes, it’s noise—but scientifically it’s changes in air pressure caused by vibration. The pressures it creates are inherently analog, that is, they’re defined in relation to something else and are continuous, with many possible states.

For humans, audible sounds are all within the range of 20 Hz to 20 kHz; the higher the value, the more “high-pitched” the sound. Think of low, rumbly bass frequencies as being near the lower bound of that range, and sharp feedback from a microphone being nearer the higher bound.

Analog vs. digital

Analog is the opposite of digital. If something’s digital, it has only two possible basic states: 0 (off) and 1 (on). Digital media is discrete (not continuous) and doesn’t allow for continuous values in the way analog does.

At this point, maybe you’re asking If sound is inherently analog, what does it mean for something to have digital sound? How can all the possible pressures of sound be represented by 0s and 1s?

The “digital” part refers only to how the sounds are represented on their storage medium, whether that’s a streaming service such as Apple Music or Spotify (either of which plays remotely stored files), a CD, or a Super Audio CD1. To create digital sound, the original analog signal is sampled: Its continuous signal is reduced to a discrete one, with each sample a “snapshot” of the signal’s amplitude at a point in time. Together, these samples, which are represented as numbers and spaced evenly in time, can be reconstructed into the original signal by a digital-to-analog converter, a small computer that converts these numbers into corresponding pressures.

I pour an inch of iced tea to match the level of the rain gauge I’m eyeballing from memory. The sound tumbles over the cubes below, its noisy current apparently familiar with the thunder, as if it’d sampled it at a low rate and shallow bit depth. Back in the waiting room before college, a lake that’d once swirled with the entirety of adulthood in its matching-color eye and beckoned for me to drown within it, had been Aral Sea’d, exposed as the aquatic emperor with its bed cracks visible to all. “Curvature, the earth, unevenness, and the wind”—a teacher’s words came through discretely as I digitally tested the lakebed for a hole to Wonderland and imagined it as the now-drunk-to-nothing cauldron of the first tea party. A Neanderthal atop a mastodon and a giant rabbit once used elaborate sluice gates, worked by pre-steam engine empowered labor, to fill this pond with glacier water and chunks and the hibiscus flowers whose pedals bled into something that already transcended Southern-ness.

If I wanted to accurately capture the sound of clinking ice cubes, let alone a collection of instruments playing simultaneously, on a digital medium, then two things determine the fidelity of my recording:

- The bit depth: You’ve likely heard something described as “8-bit,” “16-bit,” or “64-bit.” Without going too much into mathematics, this descriptor, called the bit depth, tells you how many possible values there are in the computing system in question. For the purposes of digital sound, it denotes how many possible discrete steps there are for each sample to be assigned to. For example, 16-bit audio like the standard CD has 65,536 possible steps that a sample can be assigned to.

- The sampling rate: This is simply how frequently I’m sampling (taking aural snapshots of) the original sine wave. For a CD, the sampling rate is 44,100 Hz—a strange-seeming number that nevertheless has some logic behind it: It’s the product of the squares of the first four prime numbers (2, 3, 5, and 7), which makes prime factorization easier.

Losing it over lossy-ness

What about “lossy” audio formats? What’s that, you didn’t know that most music you listen to has “lost” some of its original character, because its file size has been greatly diminished or at least compressed so that it can be transmitted over a network (like the Internet)?

MP3s, which dominated the 2000s with the advent of the iPod, are often 90% smaller than the on-disc files they were ripped from. Modern streaming services use lossy files, too, although Apple Music at least offers lossless quality—but you won’t actually get it unless you use wired headphones. Most implementations of Bluetooth are lossy and they always compress the file. Some wireless forms of transmission, like AirPlay-ing a song from an iPhone to a HomePod, are lossless because they use Wi-Fi instead of Bluetooth.

Does lossless music sound better, though? You may think there’s a huge gap in quality given the order-of-magnitude difference in size. But the human ear isn’t that discerning. The range of frequencies that a standard CD can reproduce—from 20 Hz (below the lowest key on a piano) to 20 KHz (something that most adults can’t hear)—is already outside the extremes of human perception. Plus, the algorithms that create lossy files are optimized to remove the parts we notice the least.

I’m back from the lake, soaked with the feeling of needing to look into something just as sensuous as its bygone fullness, so I’ve got a curved 1996 TV with windy signals sweeping across its face. In a later life, it’ll be dusty, birthed anew though old with nostalgic reverence, but right now it’s pristine and basic, with speakers that yield from a cartridge-loading game console a no-temperature no-color sound—anti-adjective waves, sweeping past my enlarged elf-like ears, red from excitement, with the spirit of being and doing rather than of looking and sounding and feeling. My ears once pulsing with analog cinders are cooled by digital rain that angles its math earthward. The sound began in the CO2-exhaling fires of circuit board production and then a factory blew it across the sea on a blimp of emissions, harmless by all appearances in its big boxy cartridge with just smokeless ones and zeroes inside, etched errorlessly on metal. Next up there’s a truck trek from the dock and some plastic to unwrap and discard to live an eternal life unseen, shining curvily and brokenly like that TV the moment some hypermodern post-man Nouveau Neanderthal digs it up despite the newly Venus-like pressure on Earth.

Though the struggle is seemingly won by lossy formats, what if on some other timeline the exact opposite had prevailed? What about a format that was somehow even “realer” than CD? Enter the…

Super Audio CD

Super Audio CD was meant to succeed the CD as the dominant physical music format. Most people don’t know what it is, and that’s understandable—it arrived right as the music industry was about to collapse into piracy and financialization and it confronted you with two things you’d expect from such a harbinger: Few noticeable improvements for its high cost, and aggressive copyright controls.

SACD was meant to kickstart another cycle of format replacements. The CD was approaching its 20th anniversary, cassette tapes were dying, and vinyl was dead enough that had yet to be zombified back into existence. The maturity of the CD lifecycle, as Andrew Dewaard describes in his book Derivative Media, arrived in the 1990s when there was already a nascent trend of trying to financialize music by making it more like rent (I’m sorry, a “service,” which all digital things seem to be becoming2), something that pointed to the demise of one-time physical disc and tape purchases:

Transforming music royalties into an investment strategy is not a new idea; David Bowie even sold “Bowie Bonds” to investors in 1997, based on income generated from his back catalog. “For the music industry the age of manufacture is now over,” Simon Frith claimed back in 1988, as music companies were “no longer organized around making things but depend on the creation of rights.” What is new is that those rights are now much more lucrative and have attracted much bigger financiers. As opposed to physical media, which was typically purchased only once per format, listening to music on a streaming service produces a financial transaction every time a song is played, dramatically increasing the value of older music.

The surge in piracy that accompanied the popularization of Napster in 1999-2000 undoubtedly hurt the music industry, but only one segment of it: artists. The profits they could make from selling immensely profitable LPs, CDs, and cassettes evaporated. Meanwhile, laws such as the Digital Millennium Copyright Act plus DRM controls in iTunes and the eventual “you have no control over this” total platform control of streaming services such as Spotify and Apple Music empowered labels, who exploited this crisis and funneled the entire music industry through their subscription services while paying out literal fractions of a penny for each stream.3

This labor-hostile reality, in which musicians are barely compensated for their music, skews listening to musicians who are already famous and favored by the highly centralized software algorithms that underpin streaming service interfaces. Breaking through thanks to regional radio or an unexpectedly popular CD release is no longer an option.

Given today’s context and how it compares to what came before, SACD looks now like a strange transitional form between modes of capitalist exploitation: The ownable physical product, of which it was the real attempt to create a mass-market optical disc format for audio4, and the locked-down streaming future:

- Unlike CDs, which were unencrypted, SACDs were and still are a pain to rip. They’re not recognizable by standard Windows or macOS optical drives, let alone standard CD players. You need dedicated playback hardware or else a pricey industrial solution, just as you need to pay money forever to maintain access to a music streaming service.

- But all this protection was meant in part to prevent the type of broad (and free) distribution that CDs had enabled. You couldn’t make CD-R copies of SACD discs and couldn’t easily leak their tracks to the internet.

- They also aimed to go even further than CDs had on the quality front, by radically changing both the bit depth and sampling rate components mentioned above. SACD lowers the bit depth to just 1-bit (so everything is literally “on” or “off”), but bumps the sampling rate up to over 2 MHz. So there are many, many more samples of the analog signal, but instead of each sample storing a step that could fall along thousands of possible values, it just indicates whether it’s higher or lower than the one before it. This setup was branded as Direct Stream Digital (DSD) and was designed to give a more analog feel to digital recordings.

- Finally, it allowed six discrete channels instead of the two (“stereo”) of CD. SACDs can output up to 5.1, meaning there’s the two stereo channels plus a center channel (usually for vocals), two rear channels, and a subwoofer.

The in-betweenness of SACD is embodied by how it’s a digital format that for years was easiest to play over analog connectors such as RCA jacks. The very first SACD player, the Sony SCD-1, could only play SACDs over either RCA or XLR connectors, both of which are analog. The digital optical and coaxial connectors couldn’t be used with SACD discs because they lacked bandwidth—as well as copyright protection.5 Modern hardware that can play SACDs, such as some Blu-ray players, can usually only do so via HDMI, which requires a receiver that can decode DSD, which can’t be assumed.

And for what? Does it sound better? SACD was a pivotal moment in the software-ization of music, in that its new features—aside from the 5.1 sound, if you had the right setup for it—had the inscrutability and utilitarianism of a software version update or patch. It was “moving forward” for its own sake, browbeating and exhausting listeners who had long since stopped noticing the belated improvements. Except here, they had the choice not to endure it because of the newer and cheaper MP3 and streaming markets; there’s something optimistic there, in that it reminds us that maybe someday we could break free from how shitty software has made our entire world.

When I first saw you, I knew you possessed the fiery shape to imprint yourself on my memory as if I were an inanimate disk drive—a metal machine marcher who remembers things even while unalive. Someday I too will be dust blown over a landfill, brought to faraway dumped-out ears in perfect surround sound with enough ambient heat to case an earbleed. There’s a new sun directly on earth; we’re moving through time, backward to a pre-Neanderthal era that never knew agriculture, just a forest where a woman is running in the dark underneath a sheet of rain.

-

What about vinyl? Well, it isn’t digital. It’s already analog, hence the argument of many vinyl purists that LPs are closer to the true sound of the music because there’s no digital intermediary. However, vinyl has lots of limitations compared to CD and digital files, including less dynamic range (the difference between the softest and loudest sounds), dust susceptibility, and routine quality degradation by the needle. ↩︎

-

Think of the ubiquitous Software-as-a-Service. ↩︎

-

Damon Krukowski, the drummer of Galaxie 500, once said that it’d take over 300,000 Pandora streams to generate the profit of a single LP. Years later, he confirmed that selling a mere 2,000 copies of a collectible LP yielded the same profit as 8.5 million Spotify streams. ↩︎

-

On the video side, this happened with the release of 4K UHD in 2016. For video game formats, the last one is likely to be whatever 4K-compatible ROM cartridge Nintendo concocts for the successor to the Nintendo Switch. ↩︎

-

Analog outputs don’t need copyright protection because recording that signal, which is already audible because it’s undergone digital-to-analog conversion if necessary, degrades it. Digital ones, such as HDMI, do because otherwise, someone could endlessly copy them with no loss in quality. ↩︎

-

Becoming a fountain pen guy. This is the Jinhao Shark, a $2 pen that’s refillable via cartridge, converter (included), or eye-dropper.

-

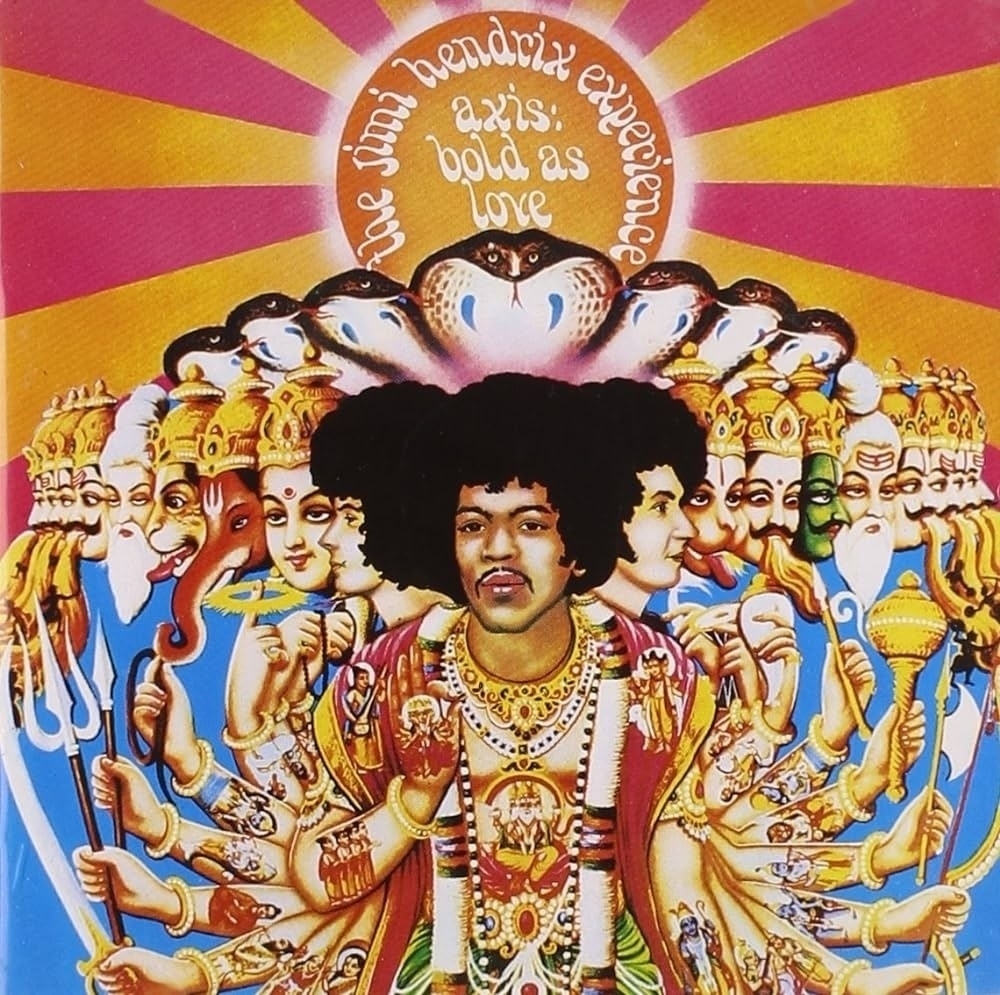

A perfect album. It gets a better “surround sound” effect from 1967-era analog stereo panning than most albums do from Dolby Atmos.